Making a Space Game and being Lazy

I was bored, and at work needed to do some drives to some places where I would be waiting in my car for anywhere from a few minutes to maybe even a couple of hours. I was never a fan of having games on my phone, and over time had some small indie RPGs or strategy games, or my golden standard, Sudoku. Back home, every few months I would dust off the digital version of Heroes of Might and Magic III, and accidentally time travel to 0500 before a full day of work. As one does, I imagined having Heroes III with me on my phone and being able to have a huge game going at all times (Very smart to lean into a dangerously time consuming activity…) I could continue whenever I had a few free minutes.

Obviously, I have to make it myself…

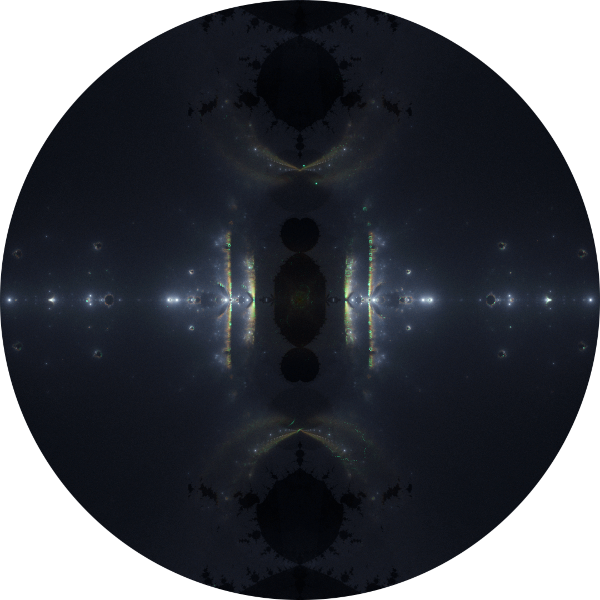

So I started the project with Godot. To minimize the amount of art assets I had to create, I decided I was going to go for a Heroes III-like in space. White pixels are stars in the background, easy money. Unit portraits I was able to find a nice set from Kenney assets, and while browsing, he also had a set of planet layers that could be combined to create nice looking planets. But I’m a smart programmer. What if I want to have 100 different planet types? What if I want a lot of different planet sizes and variations on different properties like atmosphere and maybe special resources that are visible, and how cool would it be to have it rotate? I was approaching pre-mature optimization levels of genius.

I remembered back in the Flash days and the ConvolutionFilter people having pseudo-3d spheres in some games, and I liked the effect, I finally had a use-case to apply it. Combined with Godot’s built-in FastNoiseLite which was a one-stop shop for several noise-generation algorithms, and enough parameters to be interesting, it seemed like I had my little planets project all set to take off. Why spend 2 hours making some prototype planet pictures for a personal game nobody else might ever see and continue making an actual game when you can spend 2 weeks making a planet generator and rabbithole into making an editor for them?

Spherical Distortion

Step one, create a fragment shader to take a 2D texture, and make it a sleek round ball of sphere. This step is actually fairly simple once you understand the input and output of the fragment shader, and what you want to happen. In shaders, the UV (the coordinate of the texture to draw) is mapped from 0.0 (start of the texture) to 1.0 (end of the texture), meaning that for any texture, a UV of (0.5, 0.5) will be the center of that texture, basically normalized 2D coordinates. For a spherical distortion, we want to draw the texture normally near the center of the “sphere”, and as we move to the edge of the sphere, we can see more and more of the texture squished into the same screenspace, as it wraps around the imaginary sphere we’re creating. In pixel terms - near the center, every 1 pixel we’re drawing on the screen will be roughly equal to drawing 1 pixel of the texture. Near the edges, every 1 pixel we’re drawing will be many pixels of the texture, and eventually infinity right at the edge (since we’re looking at the texture from a perpendicular perspective, we can “see” “all” of it). What is a nice equation that gets us there? arcsin of course!

As x moves to 1, the tangent moves to being vertical, and the y moves to PI / 2! Since we’ll be scaling the UV coordinates, we get a ratio by dividing the arcsin value by the original value, giving us the amount to scale by. We can also divide by PI / 2 to normalize this scaling factor within 0 <= x <= 1.

In Godot shader terms, this can look like:

vec2 spherical_distort(vec2 uv) {

float radius = length(uv);

float displacement_scale = (radius != 0.0 ? asin(radius) / radius : 0.0) / PI2; // PI2 is a PI / 2 constant

vec2 displacement = uv * displacement_scale;

return (displacement + texture_offset) * texture_scale;

}

With this function, given a UV coordinate which is centered around (0.0, 0.0), it will “push” it out as it approaches the edges of the circle. This is the basis for spherical distortion in the shader. You can also see 2 other parameters (in this case they are uniforms), texture_offset and texture_scale. The offset is what is controlling the scrolling, or “spinning” of the planet. The scale, as one could assume, is simply a zoom factor for the texture. Since it is a vector, you can stretch the texture horizontally or vertically as well.

I now had nice little spheres I could use. Job done, right?

I don’t have Scope Creep problems

As a genius programmer, it’s not enough to have something working, add it to your game and get on with it. What about all sorts of changes, I want to play around with the planets? What about generating planets based on physical parameters like humidity or temperature? Obviously, I need to create a custom GUI to easily play around with the look and feel of these planets, shouldn’t take too long, and it will speed things up in the long run.

The next few days were spent on a little editor, because I wanted to play around with how I could parametrize the planet creation based on a few properties I wanted in the game, things like water-level, humidity, temperature, and types of minerals on the planets. As I worked, I started to want more visual effects, and also easier to use UI controls. Piece by piece, I had a cluster-fridge of ambiguous goals and ideas.

An early version allowed me to modify the noise generation and color gradients. I’m controlling my scope creep, so these will be enough. I had already added specular lighting, which already felt like reaching too far, but didn’t require too many changes, so … “while I’m at it…”.

Adding height mapping and more detail

I was already happy with what this version was capable of, since my initial goal was to target a pixel-art style. It’s simpler to work with in game development terms, at least for my purposes, and the lack of too much detail meant I could be more permissive in the colors and types of planets. It’s sci-fi, after all. But after looking at the planets for a bit, it seemed janky to have a pixel-art ground texture, but a smooth high resolution outline. Do I just live with it because it’s just a prototype, the important part is progress on the game? Ha.

I started delving into high resolution planets and basing my roadmap on making them look good. They already looked satisfactory, and by using several layers with the same noise parameters, I could differentiate the water and land (at this point specular was a property of the whole layer). But getting side-tracked must not be stopped. I remembered about height mapping from earlier days when I dabbled in 3D rendering, and also having the specular as a property of the texture, with its own gradient, would make creating cool planets easier. I first thought about the amount of work to now have 3 different textures (diffuse/color, normal, specular), generating a normal map from the height texture and how these would increasingly drive the base algorithm further from being close to Godot’s built-in functionality (which was a goal). Here, Godot itself was the enabler of my journey to nowhere. Turns out there’s a CanvasTexture. This is a compound texture of, surprise, a diffuse texture, normal texture, and specular texture. Nice. And to finalize my pragmatic decision making process, Godot’s NoiseTexture can automagically generate a normal map, using the noise as a height map. Looks like I’m in for the long haul.

“Luckily”, because Godot already had these tools built-in, setting things up wasn’t too hard, but it required I revisit my gradient editing UI components. Initially these were made to just be usable, but since now I’ll be working with 3 different gradients per layer, I can’t have the interface being cluttered for the imaginary users of this tool.

I got a curve editor working, and (as one does) refactored UI code to be more compartmentalized. As it stands right now, the control points for all gradients are synchronized, so each control point of the color curve has a corresponding control point in the height and specular curves. This isn’t inherently necessary, and will probably change in the future to enable better color palette generation (there was a prototype, but we’re controlling our scope creep, so not for now) while keeping height and specular curves simple.

Nice. This should definitely be enough. And it has been, for now. There are future plans to continue development, one important low-hanging fruit would be to have export options for the textures separately (diffuse, normal, specular), at which point I can’t help but feel this slowly turning into a generic material editor. RIGHT?

Links: